On August 5, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), India’s ruling party, controversially stripped the state of Jammu and Kashmir of its autonomy. Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the Hindu-nationalist BJP have long argued that Muslim-majority Kashmir should not have special status and that the state was marred by terrorism and corruption. This development highlights the prevalence of Hindu-Muslim inter-communal tensions since the BJP took office in 2014.

While the focus on Kashmir is important, international attention on this issue is masking the ongoing disenfranchisement of a large Muslim population in Assam, a state in northeastern India. The National Register of Citizens (NRC) process has put almost 4 million people, largely Bengali Muslims, at risk of being made stateless. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees estimates that there are 10 million stateless people worldwide. With this one act, India risks becoming the home of the largest number of stateless people in the world.

What Led to the NRC?

Anti-immigration sentiments have lingered in Assam for decades, the roots of which can be traced back to India’s colonial history. After the British conquered the region in 1826, they drastically altered Assam’s demographic structure. The immigration of Bengalis from neighboring East Bengal was incentivized as the British needed workers for their agrarian base. In 1983, hundreds of Bengali Muslims were killed by Assamese nationalists during a massacre in Nellie, central Assam. Since then, there remains deep friction between these ethnic groups, affecting Assamese society to this day.

In 1985, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi signed an accord with Assamese nationalists to create a citizenship register. According to this register, anyone who entered India after midnight of March 24, 1971 (the day before Bangladesh declared its independence) was considered a foreigner. However, no real advances were made on the registry until its revival in the summer of 2018.

Failures of the NRC process

When the BJP campaigned for state elections in 2016, its manifesto was to publish the NRC as soon as possible. When the first draft of the NRC was published in the summer of 2018, it was revealed that more than 12 percent of the Assam population, or almost 4 million people (mainly of Bengali ethnicity and largely Muslim) didn’t make the cut. It is expected that the final NRC list, which is scheduled to be published on August 31, will have roughly the same number of people omitted.

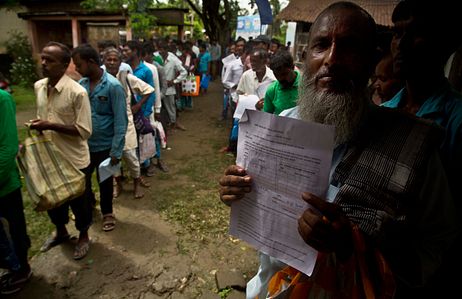

The NRC process is a highly bureaucratic and paper-based exercise. Applicants must produce proof of their family’s residence in Assam prior to 1971. Having such documentation is difficult in Assam, where 30 percent of the population are illiterate and live below the poverty line. In some cases, even army personnel have not found their names on the NRC list. This process contradicts international norms where the burden of nationality determination lies with the state not the individual.

The government has announced that those excluded from the NRC will have 120 days to appeal their cases and establish Indian citizenship in front of the appellate authority, locally known as Foreigner Tribunals. The tribunals have been criticized for being opaque and arbitrary in their proceedings and have been marred by errors. Furthermore, there is no legal provision exempting children from standing trial.

UN Rapporteurs have also commented that the lack of clarity between different processes (not just the NRC process, but also electoral roll information and separate judicial processes before the Tribunals) leads to the risk of arbitrary and biased decision-making. This is further reinforced by the BJP’s current efforts to pass the Citizenship Amendment Bill 2016, which makes it easier for immigrants from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan to obtain citizenship – as long as they are not Muslim. This clearly discriminatory bill, however, puts the BJP in tension with state officials and pressure groups in Assam who don’t want any Bengali “foreigners,” whatever their religion.

Lastly, delays could leave people living in limbo with their citizenship status in doubt for months, if not years, as appeals through the High Court and Supreme Court take place. Faced with such an abject situation, some residents have died by suicide and high rates of negative mental health have been reported.

The NRC and Potential Statelessness

The impending statelessness catastrophe in Assam has been seen before. In the 1980s the Bhutanese government stripped the Lhotshampas, a Nepali ethnic group, of their citizenship and forced them to leave the country. More recently, the Rohingyas, a stateless and mostly Muslim ethnic group residing in Myanmar, fled to Bangladesh after a wave of attacks.

Thousands of individuals in Assam are already in detention camps after having their citizenship questioned. Several new detention camps are being readied to house those expected to become stateless at the end of the month. Already dealing with the Rohingya crisis on one border, Bangladesh has expressly stated that it will not accept those India deems “foreign.” The risk of indefinite detention without any recourse looms large. Furthermore, the NRC deadline coincides with the constitutional amendments on Kashmir, begging the question: Is the BJP’s plan to keep the focus on Kashmir to ensure little scrutiny of what is happening in Assam?

As the world’s largest democracy, India paints itself on the international stage as a supporter of international norms and rule of law. But such talk is shallow if India is not held accountable for its actions. In 2017 the world was shocked at the brutality suffered by one million Rohingyas who fled violence unleashed by the Burmese military junta. A new statelessness crisis is looming in South Asia, which could affect almost 4 million people. International pressure to ensure there is due process and clarity on what happens after the NRC deadline is essential. India must safeguard the rights of all its people or the human costs will be incalculable.